, March 10, 1972, by Larry L. King

Special thanks to Garland Wood for taking the time to scan and submit this article!

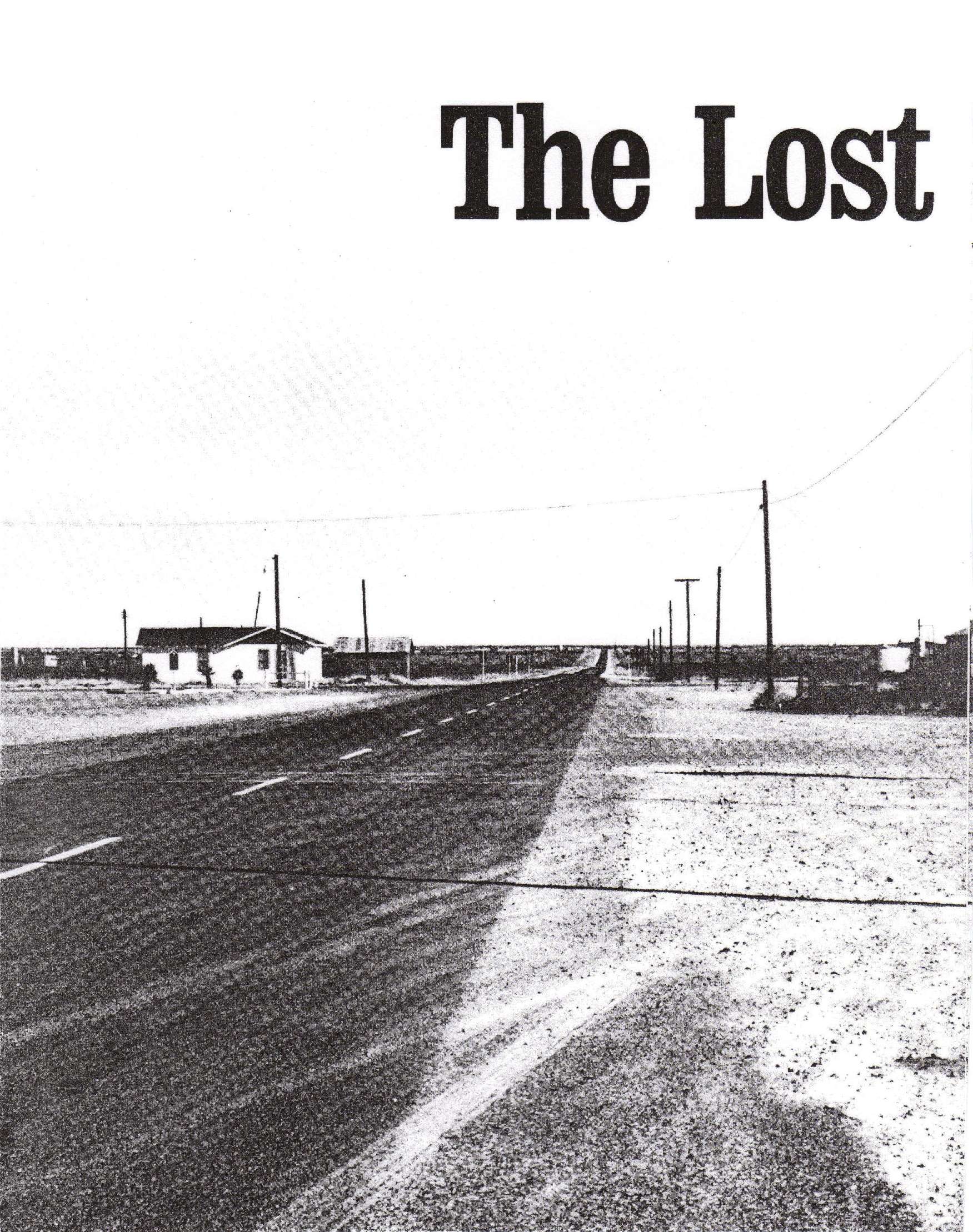

On its way to no place in particular, Texas State Highway 302 bores through the center of Mentone, county seat of

Loving County. |

The last boomer has passed by - his spirit, alas, has passed too.

As the nation moved west seeking new frontiers, Texas, a rude young empire won in blood, was inhabited by restless

and adventurous men chasing their own special dreams. One of these was Oliver Loving, a legendary cattleman who, passing

through the barren reefs adjoining New Mexico in 1867, was shot, scalped and left for dead. He crawled 18 miles, chewing

an old leather glove for sustenance, and emptied his pockets of valuables to a roving band of Mexican traders against

assurance that he would be packed in charcoal and returned east to Weatherford -- almost 500 miles -- for burial. It was

perhaps typical of the breed, the period and the place that Oliver Loving stubbornly refused to die until he had

arranged his own terms.

Our literature and our legends abound with tales of the frontier spirit, of men who lived out of saddlebags or sod

huts, carving and sweating a new civilization in which they attended their own fractures, made there own rules and

raised their sons to independent and taciturn ways. In 1893, 26 years after Oliver Loving's death, a county bordering on

New Mexico in the westernmost part of Texas was named for him. Loving County today is the most sparsely populated county

in the contiguous United States, 647 square miles with 150 people scattered among 451 producing oil wells. This is land

no less desolate than in an earlier time, and it is reasonable to suspect that the folks who remain here -- the sons and

daughters of gritty dry-gulch farmers, wild-horse tamers and oil-field roustabouts -- would naturally retain their

forebears' adventuresome pioneer spirit, coupled with their own stubborn dreams of self-fulfillment.

Once the nation drew its strength from these lower regions, masses of individual songs melding into one symphony of

hope and pride and individual doing. Now, so much in America seems to have homogenized and dulled us that it is not too

much to imagine that one day soon we shall all sound like Jack Lescoulie. Perhaps out on those few old frontiers where

there is still elbow room, we can rediscover charms, virtues and vitalities that speak well of our roots and suggest

options for our futures. These are the hopes, at least, that one can bring to an examination of Loving County.

The best place to meet Loving County's last frontiersmen is in the town of Mentone, and more specifically in Keen's

Cafe, popularly known as "Newt's and Tootsie's." Keen's is the only place in all the county where one may

purchase a beer -- or anything else of value, though they do sell marriage licenses across the street at the squat

county courthouse. On this boiling day, |

Keen's Cafe is the only place that sells beer in the whole of Loving County's 647 square miles. It's also the

communal center for 150 residents. |

Better the lawman had come to poison the water

Weepin' Willie Nelson is warning on Newt Keen's jukebox of all the gratuitous troubles love provides when another

kind of trouble --wearing a big-brimmed hat and a snub-nosed pistol --clatters through the front screen door.

Garnville Lacy, ruddy-faced to the bone, is toting the snub-nosed pistol under the aegis of the Texas Liquor Control

Board. He has driven from Odessa across 78 miles of burning desert sands -- past oil-well pumps, nodding their rich

extractions like gentled rocking horses, and past infrequent hardscrabble ranches -- to serve a seven-day suspension

notice of the beer permit entrusted to Keen's Cafe.

Newt Keen, proprietor, is a graying former cowboy with jug ears and a sly country grin that says he knows the joke

and the joke is not on him. He seem to harbor some secret mirth, a submerged mysterious bubbling that has survived

tornado funnels, droughts, bedroll rattlesnakes, rodeo fractures and the purchase of a ranch from a salty old pioneer

woman who, it developed, did not own a ranch to sell. Equipped by seasoning and history to expertly sense disaster in

its many forms, Newt, on spotting the lawman, mumbles, "Oh, hail far! It's liable to get a whole lot drier around

here."

Newt greets the liquor agent aloud, however, as if in the hire of Welcome Wagon: "Come in! Come in! Y'awl been

getting any rain over your way?" He crashes about in scuffed cowboy boots, his body a tad stooped as if permanently

saddle-sore, and offers the lawman a mug of thick coffee.

Granville Lacy sits at one of the two rickety counter between a factory-tooled sign instructing: AMERICA, LOVE IT OR

LEAVE IT! and a homemade sign running alternately uphill and down, as if maybe it had been painted in the dark: OUR BEER

LICENSE DEPENDS ON YOUR GOOD CONDUCT. The six other customers in the cafe, which seats a maximum of 20, watch the lawman

with obvious distaste and apprehension.

"Mr. Keen," the lawman says, "I've got some papers to serve on you."

Conveniently deaf, Newt gestures toward the coffee he's poured Lacy: "You want me to cripple that with a little

dab of cream? Looks like it was dredged up from the Pecos River bottom." A head shake. Newt tries again:

"How's them two big old boys of yours? They doing all right?" Above the counter are likenesses of Newt's own

two older sons, Vietnam veterans, proudly in uniform.

The liquor agent unfurls and crackles his official documents: "Now, Mr Keen, this temporary suspension begins

next Monday..." But Newt is clomping across the wooden floor to replenish beer supplies and honor orders for

cheeseburgers or chicken-fried steaks with cream gravy.

Agent Lacy inspects his papers while Newt relays food orders to his red-haired wife. Tootsie, who retains a high

faith in beehive hairdos. The jukebox has fallen dumb, permitting the lawman to better sample a united community

hostility among the oil-field workers and ranchers. It is one thing to retard the flow of alcoholic comforts in any one

of Manhattan's countless aid stations --or even one of Odessa's -- but it is quite a deeper sin to dry up the only

watering hole in all of Loving County. Newt and Tootsie dispense approximately 50 cases of beer each week; a shutdown

theoretically would meanly deprive every man, woman and child in the county of eight bottles or cans. Better Granville

Lacy had come to town to poison the water, which leads on the believe that Sheriff Elgin "Punk" Jones --who

reported the infraction -- will have to pay for his nefarious deed.

When Newt Keen next passes within range, the liquor agent reads in a low monotone: ...

did on the some-oddth day of August, 1971, in violation of section this, paragraph so-and-

so...

Newt shuffles, pulls an ear, shoot concerned glances at Tootsie. She attends her griddle with jerky motions of anger,

slapping hamburger patties with unusual vigor...

nor sell, nor give, nor consume, nor allow to be consumed, any alcoholic beverage on said premise

until.... Wearing the abashed grin of an erring schoolboy, Newt laboriously scratches his signature. |

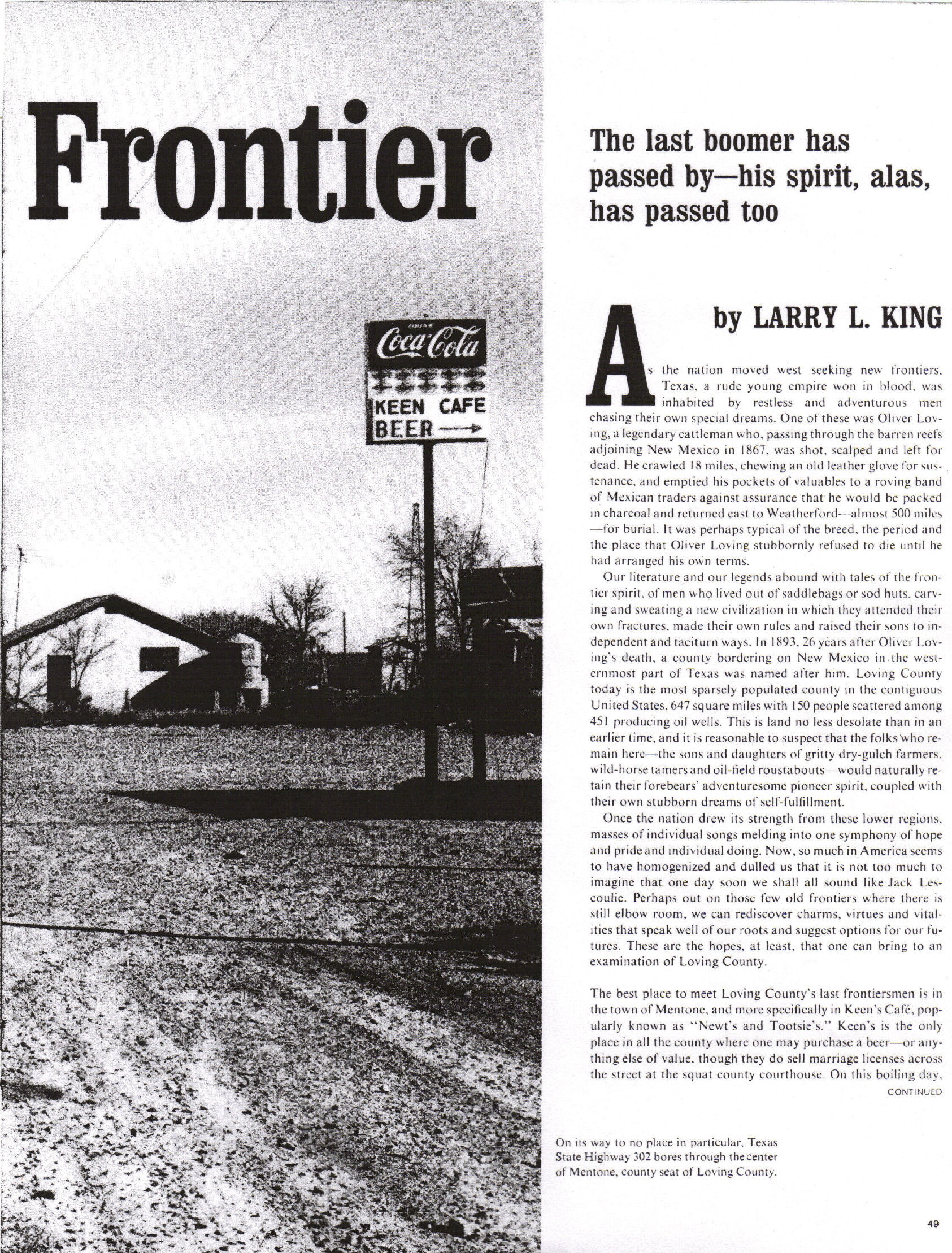

Cafe owners Newt and Tootsie Keen trade familiar jokes and fresh gossip with coyote hunter Bob Weaver |

'We'll claim cruel and unusual punishment!'

Newt's formal surrender seemingly reassures the lawman, who jovially says: "Now I got another complaint. You've

got four beer signs outside, and you're not allowed but two."

"Four? I can't count but three."

"Naw, four. Your main sign counts as two. One for each side of the sign."

Newt, uncertain of the bureaucratic bogs, says, "Well, what's the big gripe?"

"Congestion."

Newt is mute and uncomprehending. This is happening to him in downtown Mentone -- population 44 -- where from any

vantage point one can see for three days in all directions and still have nothing to tell. He gazes across all that

empty territory until his eyes lock on a distant windmill. "Well," he finally drawls, "I sure would hat

to cause any traffic jams." When the locals snigger over their well-catsuped home fries, the lawman reddens:

"We've got no choice but to enforce the law. It's an old law the church folks got passed back in the '30s." He

makes it out the door unaided by any understanding nods.

Before the lawman's dust departs, all the customers compete to damn the prying old government. Warren Burnett, a

prominent Texas lawyer who has paused at the cafe in mid-passage to El Paso, offers to represent Newt for free should he

wish to fight the suspension order: "We'll claim cruel and unusual punishment! A man could die of thirst out here.

Hell, Newt, your place is more than a community center -- it's an

outpost, by God, offering new beginnings and shelter against the elements ..."

"Do it, Newt." Tootsie said.

"Naw, I got to live with that old boy. Besides, this ain't his fault."

"Well," the lawyer said, "come next Monday it'll be a long hot path to beer. So whose fault is

it?"

Newt drawls it out like

Gunsmoke's Festus: "Accordin' to that batch of official papers, it's mine!" After

the laughter abate, he says, "Aw, one night a while back we got to dancing and barking at the moon in here and,

well, maybe we run a little past closing time. Mister, I been in this country since the sun wasn't no bigger than a

orange and there wasn't no moon a-tall and windmills wasn't but waist-high, and I've learnt that when you can

sell something out here -- you better not worry about what time it is."

Tootsie says: "That ain't the whole story."

"Well, okay, Mama. Awright, I was drinking nearly as much as I was selling and business wasn't too bad. The

sheriff -- old Punk Jones -- he come in and caught me and snitched to the liquor board."

"You oughta run for sheriff yourself, Newt," one of the locals suggests.

"Naw sir." Newt says, "I ain't gonna say a mumblin' word against old Punk -- right on up to election

day." Appreciating the laughter, he fishes in icy waters and pops himself a beer. "Punk, he don't have nothing

to do but enforce the closing laws in this one little old place, and I sure wouldn't wanta interfere with law and order

here in Loving County."

The dominant political strain in Loving County runs to an abiding conservatism. The natives -- well-off and poor

alike -- reject anything smacking of charity, and so they regard federal aid as being no less poisonous than the ever-

present rattlesnake. When a federal court instructed every county in Texas to participate in the Family Food Assistance

Program for the poor, Loving County Judge W. T. "Bill" Winston said: "We don't need it, we don't want it,

and we can't use it if we're force to take it." Snorting and jiggling his beer glass in Newt's and Tootsie's now,

Judge Winston gloomily says, "They finally forced it on us. We've got nine people getting it -- seven in one

family. And they're Mexicans." When the Department of Health Education and Welfare ordered the county to either

racially |

The land in Loving County is dry, flat, melancholy, with only an occasional building to break the horizon |

'Let's face it, it's boring here'

integrate Mentone's 16-pupil school or lose its federal money. Judge Winston fired off a terse letter informing

Washington that Loving County: (1) had no black residents; (2) had never received a dime's worth of federal school aid;

and (3) didn't covet any.

Television has brought the problems of New York, Watts and Saigon to the attention of the neglected territory.

Everybody worries about blacks or dope or crime or the Vietcong just as if they had some. Newt Keen no longer goes off

and leaves his cafe doors unlocked to accommodate stray customers because "you can't tell when somebody might come

over from Monahans or Pyote and clean you out." But the Mentone jail has not had a customer in seven years, and

Loving County's crime wave last year consisted of a profitless burglary of the schoolhouse and the theft of several

rolls of steel cable from an oil lease.

Ann Blair, a pretty young blond who works in the courthouse for her mother, County Clerk Edna Clayton, frets that the

outside world may taint her two small children. "Let's face it, it's boring here for adults, but there's no better

place to raise kids." says Ann, a graduate of Odessa Junior College. "We have a good family life. My fifth-

grade boy has learned work and the value of a dollar. When I went off to college, I saw wild kids and all kinds of

temptation. And it's so much worse now, with drugs and sex crimes."

Inconvenience is taken for granted. The nearest movie house, beauty shop, physician, lawyer, bank, weekly newspaper,

cemetery or grocery store is from 55 to 90 round-trip miles away. Fifteen of 16 Mentone School pupils are bused in from

six to 60 miles away. Sixth-graders and above are bused almost 80 round-trip miles to Wink.

Despite the riches of oil and gas under the earth, each Loving County family must provide its own bottled-gas system.

And there is no public water supply. Water is hauled in a tank from Pecos at 50 cents per barrel. Even cattle balk at

drinking the brackish product of the Pecos River, long ago polluted by potash interests in upstream New Mexico, a fact

that, surprisingly, no one here rails against even though their forebears always raised hell at anything - fences, sheep

herds, squatters -- infringing on their freedoms or presuming to prosper at their expense.

The land is stark and flat and treeless, altogether as bleak and spare as Russian literature, a great dry-docked

ocean with small swells of hummocky tan sand dunes or humbacked rocky knolls that change colors with the hour and the

shadows: reddish brown, slate gray, bruise-colored. But it is the sky -- God-high and pale, like a blue chenille

bedspread bleached by seasons in the sun -- that dominates. There is simply

too much sky. Men grow small in its presence and -- perhaps feeling diminished -- they

sometimes are compelled to proclaim themselves in wild or berserk ways. Alone in those remote voids, one may suddenly

half-believe he is the last man on earth and go in frantic search of the tribe. "Desert fever," the natives

call it.

And while the endless dry doomed land and eternal sky may bring on the fever, so, too, can the weather. The wind,

persistent and unengageable for half the year, swooshes unencumbered from the northernmost Great Plains, howling,

whining, singing off-key and covering everything with a maddening grainy down. Court records attest that during the

windy seasons the natives are quicker to lift their voices, or their fists, or even their guns, in rage.

The summer sun is as merciless as a loan shark: a blinding, angry orange explosion baking the land's sparse grasses

and |

Sheriff Elgin "Punk" Jones has not locked up anyone in his jail for seven years |

Those who can, move on when they can

quickly aging the skin. In winter there are nights to ache the bone, cold, stinging lashings of frozen rain. Yet ever

the weather is not the worst natural enemy. Outside the industrial sprawl of the prairie's minicities -- on the

occasional ranches or oil leases or in the flawed little country towns -- the great curse is boredom. Teen-agers in the

faded jeans and glistening ducktail hairstyles of another day wander in restless packs to the roller rink or circle root

beer stands sounding their mating calls by a mighty revving of engines. Old men shuffle dominoes in the shade of service

stations or feed stores. There is the television, of course, and the joys of small-town gossip -- and in season a weekly

high school football game may be secretly considered more important than even Vacation Bible School. Newt Keen laments

the passing of country socials where people reveled all night at one ranch house or another: "Now you got to go

over to Pecos to them fightin' and dancin' clubs. But, you know, it ain't near as much fun to fight with

strangers."

The young and the imaginative in Loving County are largely disaffected, strangers in Jerusalem. And those who can,

move on when they can. Today's desert youths belong to a transitional generation. Born to an exhausted frontier where

there are no more Dodge Citys to tame, no more wild rivers to ford, no more cattle trails to ride or oil booms to

follow, theirs is a heritage beyond preserving. The last horseman has passed by, leaving only myths and fences.

Industrialization has come and gone: having drilled and robbed the earth, the swaggering two-fisted oil boomer, heir

apparent to the earlier cowboy or Indian fighter, has clattered off to the next feverish adventure, leaving behind

sterile sophisticated pumps and gauges and storage tanks that automatically record their own dull technological

accomplishments. Only the land remains, the high sky, the eerie isolation. The wind hums mocking tunes of loss and the

jukeboxes echo it: "...Just call Lonesome-seven-seven-two-oh-three..." "I'd trade all of my tomorrows for

just one yesterday...."

The songs are of rejection, disappointment, aborted opportunities...of finishing second. And the music is everywhere,

incessantly jangling, the call of the lonely. Even many graybeards who have trimmed back their dreams -- if they ever

had any -- cannot sit still unless the jukebox or radio is moaning to them of unrequited love, of the tricks of the

wicked cities, of life's rough and rocky traveling. Few know that the music says more about them than they say of

themselves.

The young sense the loss of a grander and more adventurous past. It is these -- the young and those who secretly know

they never will be truly young again -- who prove most susceptible to fits of desert fever. And so they sometimes go

lickety-split down the rural highways at speeds dizzy enough to confuse the ambidextrous, running like so many Rabbit

Angstroms, leaving behind a trail of sad country songs, beer vapors and the echo of some feverish, senseless shout. Some

may find themselves at dawn howling in the precincts of a long-forgotten girl friend, or tempting the dangers of the

"fightin' and dancin' clubs." Some keep running: to the army or to a Fort Worth factory or maybe to exotic

Kansas City. Others, their fevers cooled and with no place to go, drive back slowly -- a bit sheepishly -- to join the

private chaos and public tediums of their lives.

Newt Keen's son Jack begins to boot-stomp across the wooden floor in a jukebox dance with a tall visiting airline

hostess. Jack is dipping snuff and wearing an outsized silver belt buckle he has won riding bulls. Over the whines and

thumps of the music he regrets that after next weekend he can't rise at a 4:30 each morning to cowboy on one of the area

ranches because school is imminent. Jack does not appear to be real partial to school, where they take a dim view of 12-

year old, 83-pound boys who appreciate snuff more than arithmetic. To somebody who first dipped at age 5, who slew his

first snake at 7 and who is impatient to ramrod his own ranch, the arbitrary restrictions on scholars can be mighty

vexing.

Tootsie worries about her son. "Till school takes up, Jack's the only kid in Mentone. The rest live on ranches

or oil leases. All he's ever been around is adults and he don't get along real well with kids." Jack proves his

mother right on the second day of school, decking another boy who has earned his disapproval. Jack's reward is three

licks from the principal's paddle. "It stung," he admits, taking a pinch of Copenhagen from his personal tin.

"I got to sign the paddle, though. You ain't allowed to sign is unless you been whupped with it."

"What'd you hit that boy for?" Tootsie demands.

Busy roping a cane-bottomes chair, Jack says, "Aw, he's about half silly."

"Yes, but what'd he do, look at you crosseyed? Jack, dammit, stop roping them chairs. This ain't no rodeo

arena."

Disengaging his lariat, Jack says, "He put his hands on my book."

"Oh," Tootsie says, apparently mollified.

Newt is amused: "Jack despises school much as I do a rattlesnake. He swears he's gonna quit when he gits to

sixth grade."

"Or the seventh," Jack says. "Maybe the eighth."

"Why, Jack," Newt says, "you're liable to wind up a full professor. What's got into you?"

The boy, vaguely embarrased, tilts his western hat over his eyes: "Mr. Knott says sixth grade ain't enough

anymore."

Charles Knott, 43, is the new schoolteacher in Mentone. When asked why in mid-career he has deserted El Paso's modern

school system for the lesser ecstasies of Loving County, he says, "I like small towns. I had 30-odd kids to the

class in El Paso, damn few of them Anglos. The kids here are eager. You take little Jack Keen. Now, he may wind up

ranching and live here all his life. If he wants that -- well, fine. But he ought to have options. He ought to know that

another life exists. You know, kids from small towns -- well, there just seems to be more to them. I grew up in a little

old East Texas town -- one picture show and a one-gallus night watchman. And a higher percentage of the kids there made

it than ever will make it in El Paso. They were more aware of themselves, aware of life. Maybe it's nurturing their

isolation, having time to think things through. Whatever, I think small-town kids use more of their potential."

The next day, as school lets out, Tootsie is gazing through the shimmying heatwaves when suddenly she say, "

My Lord, little Jack must be sick. Yonder he comes wagging his school books home with

him." Apparently she doesn't realize that Jack may have a growing dream. |

Snuff-dipping Jack Keen, age 12, is literally the only kid in town |

Once they would have drunk when thirsty, by God

Day after day, as the suspension lengthens, the mood in Newt's and Tootsie's beerless free-enterprise cafe grows more

and more subdued. Since the suspension, Sheriff Punk Jones -- who rose to his present eminence after serving as

courthouse janitor -- has begun to hear rumors that a disgruntled Newt Keen might oppose him on the ballot after all. A

good country politician who knows that a handful of votes might return a sheriff to mopping the courthouse, Punk Jones

begins to stress the vast stores of bookwork attending his office; it is well known that Newt's painfully concocted

customers' checks for chili or cheeseburgers require more translations that the Rosetta Stone.

In the cafe, customers are infrequent. Those who drop in jangle around aimlessly, some lamenting the lack of liquid

comforts with the sorrow of one whose dog has died. Tootsie sits at a table near the soundless jukebox, making do with

coffee. Abruptly, she says to her husband behind the counter, "Newt, what we doing in this fool cafe business

anyhow?"

"Well, hon, I just plain tard of being governor, and the gold-mining business was boring me."

Irked, Tootsie helplessly shakes her head. Daring for once to question life's random assignments, her reward is

another of Newt's drawling jokes. One has the impression she suddenly requires answers to questions that did not exist

for her before. Something in the restless sweeping of her eyes hints that she has come on some new, if myopic,

vision.

"We've made a living," Newt defends, walking over and putting a quarter in the jukebox.

"Yeah," Tootsie says, "I don't buy a whole lot of diamonds."

"Naw, Mama, but you don't live in some old line shack and cook for the range camp neither." They are

silent while Willie Nelson sings of how "it's a Bloody Mary mornin' since baby left me without warnin' sometime in

the night..." "Say," Newt says, "you remember when we was fresh married and lived in that old dirt-

floor dugout?" Tootsie nods, smiling, he face softened by some special old memory. "Well, hon, I always wanted

to ask you something about that: when you snuggled up so close to me that first winter, was it on account of you loved

me so much or because you was scared of the rats?"

In a monotone as flat as sourdough biscuits, she says, "I was scared of the rats." They look at each other

and laugh.

"All this will straighten out in a day or two," Newt promises, seeming to have missed the point of her

question, her mood.

"Hail, we got more food business that we do beer sales."

He shuffles over and sits beside Tootsie who is stirring her mug of thick coffee at the table. The two of them gaze

out the screen door at the lost frontier. Nothing, absolutely nothing, is moving on the ribbon-straight highway. They

sit and stare, their faces in repose as melancholy as a plain old three-chord hurtin' country song, while Eddy Arnold

croons to them of big bouquets of roses.

Something old and precious and a close kinsman to steel -- some abiding chemistry of hope and grit -- seems to have

disappeared from the frontier blood. The men who shaped and settled this desolate waste relied on a fierce, near-savage

independence coupled with a vision that made them feel captains of their own fate. That vigor, that vision, is gone now,

as exhausted as the frontier itself.

It is sad to see people so tamed and hobbled and timid and dreamless in a land born wild. The descendants of the old

breed may roar like wounded lions at distant menaces -- the pretensions of sociologists, the pious prattlings of

politicians, the mod and the unfamiliar -- but they grapple ineffectually with their immediate concerns, their boredoms,

small, mean jobs, polluted rivers and officious bureaucrats. In the old days, the people simply would not have tolerated

the closing down of their only communal outpost: No, they would have told Punk Jones that they would drink when thirsty,

by God, no matter the preferences of some chair-bound Austin bureaucrat with nothing better to do than sign suspension

orders. This lethargic acceptance of fate's happenstance gifts, with no more than a shrug or a token grip, gives one the

sense of being a visitor at a wake, of witnessing some final burial of the spirit, of watching people without purpose

merely getting through another day. Frontiers were made for better uses.

Still, on does encounter qualities to admire and enjoy here. A withered rancher who will identify himself only as

"Jesse" contentedly saws into one of Tootsie's steaks and says, "This country's

soothin'. The country's close to you out here. You feel a kinship with it. It don't

have no boundaries." Newt Keen says of his neighbors:

"We come together like a family when there's trouble. You take over here in Kermit" -- he jerks a thumb toward

the highway -- "this stranded family stopped at a church one Sunday to ask for a little food and gas money. All they

got was a promise the congregation would pray for 'em. Well, they limped on over here. We supplied 'em a big box of

groceries and took up a collection for gas."

There is little Jack Keen, who probably has spunk and survival instincts superior to most children and surely has

more room to discover himself. Some essence of the pioneer woman's endurance survives in Tootsie. Newt is improbably

cheerful in a time full of frowning; he at once preserves the old colloquialisms and speaks a native American

poetry.

That much has survived, and must be clung to. But over the years, generation by generation, the resources and the

spirit of Loving County have been dried up, and there is a lesson to be learned here. As in the nation as a whole, each

generation spoke much and thought little of the future requirements of its heirs.

Hereafter, we must plan far better with far less. |