Hurricanes

Names of Major Storms:

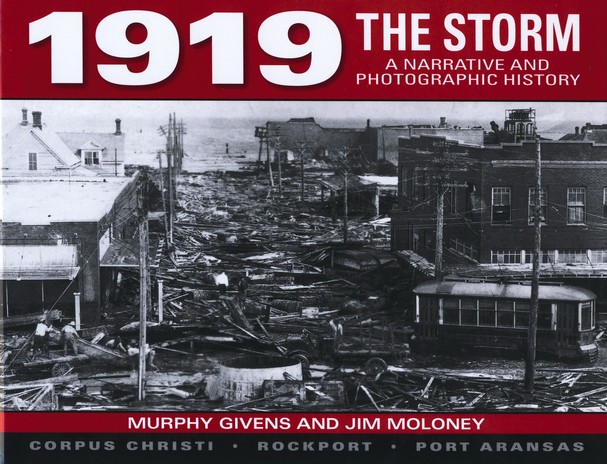

Hurricane of 1919

In 1919, Port Aransas, Rockport, and Corpus Christi were enjoying an economy bolstered by increased tourism into the area during the peak summer months. Further aided by the widespread belief that the Coastal Bend was protected from the severe damage of hurricanes by the barrier islands, the region was indeed enjoying unprecedented growth. Even when the stories of incredible damage from a hurricane in the Florida Keys reached the area, little was made of the possibility of a Texas landfall by either the local citizens or the Weather Bureau. If fact, all indications at the time pointed to the hurricane curving into the Louisiana coastline as late as the 13th, the day before landfall in Texas.

With the advantages of radar, satellite, and weather balloon reports, it seems to be almost inconceivable today that we have not always had the luxury of tracking hurricanes. But what was a real fear in 1919 became reality when the Weather Bureau lost the hurricane in the Gulf on the afternoon of the 13th. With no ship reports and only sporadic observations along the coastline, the Weather Bureau began a desperate attempt to find the hurricane center. Coastal offices sent special observations by telegraph every two hours to the Washington headquarters. At midnight on the 13th, little indication of the storm's location could be found. Wanting to take all reasonable cautions, the headquarters in Washington called for the Corpus Christi office to "take all possible precautions against rising winds and higher tides especially if [the] barometer begins to fall steadily".

Through the night, the barometer began a steady fall and at 8 am stood near 29.40 inches. Northwest winds through the night had increased to 46 mph, and a constant rain had begun falling. At 9:30 am, the Meteorologist-In-Charge of the Corpus Christi Office issued a statement to get people out of low lying areas. Police, city, and Weather Bureau official began to notify the public. Confirmation of the storms approached was received by the office at 10:30 am, when the regional Weather Bureau Office warned of the storm location very near Corpus Christi. Shortly there after, wires to Port Aransas went down, isolating the city of Corpus Christi. Rockport did receive later advisories, and the last one received gave an accurate if not cryptic analysis to the storm - - 'This is the worst hurricane in History'.

The height of the storm exacted a rare third effect on the Coastal Bend coastline. The first two deadly effects, the storm surge and wind, act to weaken and then tear away buildings close to the coastline. But with the track and strength of the hurricane, a seiche [a standing wave that moves back and forth in a body of water that is partially or fully enclosed] developed along the bayfront region of Corpus Christi. A seiche is best demonstrated by taking a cup of water and blowing on the surface. The water will rise and ripple against the far side of your cup. When you stop blowing, the 'build-up' of water on that side will move back and forth in an attempt to find an equilibrium. During the Hurricane of 1919, a northeast wind developed a seiche. As the wind veered to the east, the seiche caused an even greater height in the storm surge. In all, the water reached 11.5 feet in the downtown district, and even higher as the bay narrows inland into Nueces Bay.

No one can give a reliable estimate of the strength of the hurricane when it made landfall on the Texas Coast. It is believed the center of the hurricane made landfall about 30 miles south of Corpus Christi, but no one lived in that region of the Coastal Bend. Wind data at the Corpus Christi Weather Bureau Office was lost in the early afternoon when the anemometer was destroyed, and the only other record of wind in the region was at the Nueces County Courthouse. The latter anemometer recorded a wind gust of 170 mph before being destroyed. This wind instrument was located on top of the building, so any data it recorded is probably too high to believe, but it does illustrate the incredible forces at work within this hurricane.

Damage along the coast was both catastrophic and deadly. In Rockport, only two houses along the coastline received relatively little damage. In the North Beach area of Corpus Christi, only two buildings survived, and both took severe damage. Debris piled up to 15.5 feet in the downtown area of Corpus Christi. 121 bodies and 87 survivors were washed 7 miles across Nueces Bay onto White's Point. Official totals of 287 dead are believed to be actually in the range of 600 to 1,000, since city officials wished to downplay the severity of the event. Corpus Christi was in the running to receive a deep water port. Such terrible disasters would only delay if not kill any plans to dredge Corpus Christi Bay. 20 million dollars in damage occurred to the area, an incredible toll for that time period. Oil tanks in Port Aransas breached during the storm, allowing a heavy crude oil into the bay. People swept into the bay as well as buildings and debris were covered in this heavy crude oil. While the crude oil caused many problems, it likely spared many lives due to the increased preservation state of the oil covered bodies. This caused a much lower rate of disease than was observed during similar disasters of the time. Some of the other damage included the downtown area being littered by some 1400 bales of cotton awaiting shipment, wreaked homes, dead livestock, and corpses that continued to wash up for weeks after the hurricane.

The personal stories of the survivors bring about a sense of astonishment and sadness. One woman was found passed out at White's Point tarred and feathered. She had become immersed in the heavy oil while drifting on debris in Nueces Bay. When she washed up at White's Point exhausted, she grabbed a pillow nearby and fell asleep on the beach. The pillow was, of course, made of feathered-down and had been ripped during the hurricane.

A second woman was washed into the Nueces Bay by the hurricane with her dog. Three times she fell off of the make-shift raft of debris and into the water. Each time the dog saved her life by pulling her by her hair to more debris. Finally, the dog fell into the water, but the owner was unable to save the poor dog. An hour later, the woman washed upon the shore at White's Point. Her husband and son were reunited with her after four days of searching, but the dog was never found.

One of the more interesting landmarks left by the hurricane was the windmill at the Fulton Mansion. The Fulton Mansion has been the landmark building for the town of Fulton since the late 1800's. The large three story building, which still stands today, held a large plot of prime land adjacent to the Fulton Beach along Aransas Bay. In 1887, a new Woomanses & Hewitt Windmill was purchased and installed in the mansion grounds. The ad from the time period proclaimed 'The tower is strong, simple and cheap', and furthermore, 'Our mills are fully warranted, and warranty is good'. The warranty probably did not apply to the fate of this wind mill. The windmill was destroyed during the height of the hurricane, and the windmill fan became airborne. Traveling approximately 100 to 150 yards, the blades of the wind mill were embedded and wrapped into an oak tree about 12 feet above the ground. The fan was embedded into the tree to such an extent that removing the blades would kill the tree. The tree now stands on private property adjacent to the Fulton Mansion, on Timothy St.

Surfing A Storm

Materials on this site are provided for the free use of persons who are researching their family history. The electronic pages on this site may not be reproduced in any format for profit.

Website maintained by Nueces County Coordinator

Copyright © 2024 The TXGenWeb Project & contributors. All rights reserved.