Two Sixshooters and a Sunbonnet

The Story of Sally Skull

by Dan Kilgore

Reprinted by permission from Publications of the Texas

Folklore Society Number XLIII, Legendary Ladies of Texas

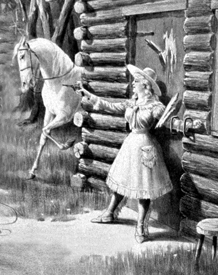

The band of cowmen critically eyed the herd of horses approaching through the opening in the chaparral, scanning each rib and hip for a familiar mark among the intricate brands denoting the Mexican origin of the horses. High crowned sombreros with their wide flaring brims told the common heritage of the vaqueros trailing the herd. But a slatted sunbonnet shielded the hawk-like nose of the slight figure that spurred ahead to deal with the riders lined across the trail.

"Sally, we're missing some horses and we. . .." "Get around those horses; you don't cut my herds."

The piercing, steel-blue eyes under the bonnet's brim spoke with as much authority as her decided tone and the two cap-and-ball revolvers strapped at her waist. The horses continued along unmolested as the cowmen eased their mounts aside. They all knew Sally Skull by reputation and chose not to cross her. Sally Skull made her own rules and defied convention in many ways other than riding astride when society dictated that ladies use only sidesaddles. A superb horsewoman, she roped and rode as well as any man. She could pick flowers with her blacksnake whip or with equal nonchalance leave the plaited imprint of its thong across the shoulders of an obstreperous man. Her language was strong and she was rated a champion cusser, her aim over the sight of either of the two sixshooters at her belt was true, and she delighted in either an evening of draw poker or of dancing at a fandango. In all, she took five husbands, and according to old legends, shot one of them and died at the hands of the last.

From the meager and scattered writings about Sally Skull, it would seem that she appeared in Texas fully armed during the 1850's to act out her violent role of cussing, fighting, and loving until she disappeared following the Civil War. In reality, she lived in the state throughout its most romantic and agonizing era, from the waning days of the Spanish empire in America to the time when the Union was sealed by the terrible war between brothers. She came to Texas as a child with the first Anglo-Americans who settled Austin's colony, fled with her babe before Santa Anna's army while her husband fought to conquer the tyrant at San Jacinto, and worked to keep the Confederacy alive with her wagon trains. A restless soul, she ranged the trails all along the great arc of the Texas coast, and years before the first shot was fired at Fort Sumter, knew every meander in what became the lifeline of the Confederacy, the Cotton Road.

She has survived as a true folk character, through snatches of information recorded by some who knew her, in stories passed down among her many relatives and descendants, and by often embroidered tales of her escapades appearing in books and magazine articles. But beyond the tales that have come down orally, solid pieces of evidence about her activities show up in official records. She resided, worked and litigated in numerous areas of Texas from the Colorado River to the Rio Grande. Documentation of at least one incident in her life is buried in some recess of the courthouse of almost every county that existed in her day. And the roots of her wild and adventurous spirit come out in the chronicles of her pioneering forebears as they followed the long trail to Texas. Sally's ancestors rode in the vanguard of pioneers who opened the American frontier. Her grandfather, William Rabb, learned the miller's trade from his uncle in western Pennsylvania, and as the line of settlement advanced, followed his trade west and then south into Spanish territory. He, his grown children, and his grandchildren arrived in Texas with the earliest settlers in Austin's colony. Perhaps his annual keel-boat trips as a youth from Pennsylvania down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to market his uncle's production of flour and rye whiskey at New Orleans kindled his desire to settle a new and farther country.

In 1801 Rabb moved his young family northwest from Pennsylvania into the Ohio Territory on the initial leg of a twenty-year journey ending in Texas. Five years later his family increased with the marriage in Warren County, Ohio, of his oldest child and only daughter, Rachel, to Joseph Newman of North Carolina. Before 1810 William Rabb with his five children and grandchildren moved on to the Illinois Territory. He erected a four-story frame water mill with four grinding stones on a stream thirty or forty miles east of St. Louis, opened a store, and filled the office of judge of the court of common pleas. When Fort Russell was erected near the Rabb home during the War of 1812, Joseph Newman enlisted in a small cavalry company that waged a bloody campaign against the Indians. In 1817, the fifth of Joseph and Rachel Newman's ten children was born and christened Sarah Jane, but is remembered today as Sally Skull.

The financial panic of 1818 forced the Rabbs far southward out of the Illinois country to what was then Miller County, Arkansas Territory, but is now eastern Oklahoma. William may have built a mill in Miller County during his sojourn there but soon was forced to move again when his land was ceded to Choctaw Indians. He and his neighbors shifted their families only a short distance south across the Red River into the Spanish province of Texas in 1820. During his stay in Illinois, Rabb probably knew or at least had heard of Moses Austin, who along with his other ventures operated a lead mine 60 miles south of St. Louis. As the leading stockholder in the Bank of St. Louis, Austin was wiped out when the bank collapsed in 1819. In a desperate attempt to recoup his fortune, Austin succeeded in obtaining a grant in December, 1820, from the Spanish governor of Texas to settle a colony along the Colorado and Brazos Rivers.

It appears that Rabb and his neighbors learned of the new colony as Austin journeyed home and spread the word on his route through Arkansas. His family, along with other residents of the Miller County area, was among the earliest colonists. Rabb received the largest grant in the colony, including the present site of La Grange in Fayette County, in exchange for his commitment to build a gristmill and sawmill on the Colorado River. The Rabb sons made at least one preliminary trip to Texas to erect a house for the large family contingent, including six-year-old Sally, that arrived on the Colorado near present La Grange in December, 1823. Indians noted their arrival by stealing all the horses except one padlocked with a chain to the log house. During the early years of the colony, Indians remained a constant threat, prowling around the houses at night to steal what they hadn't begged during the day. When husbands were away at night, wives often blew out the candles and put the children to bed for fear the savages would shoot them through cracks between the logs of the cabin.

Some of the earliest tales of Sally and her family involve Indian episodes. Doors of the log houses often did not touch the floor and when one enterprising Indian thrust his feet in the opening to raise the door from its hinges, Rachel Newman removed his toes with one chop of an ax. On another occasion when the intruders decided to enter down the chimney, Rachel kindled the contents of a feather pillow in the fireplace to smoke them out. A few years after she arrived in Texas, young Sally first assumed a man's place in the world when she observed two Indians creeping toward the house. She, her mother and a sister were alone with a male visitor, who was not one of the family. The frightened man removed the lock from his gun and pretended it was broken. "I wish I was two men," he said, "then I would fight those Indians." "If you were one man," cried Sally, "you would fight them. Give me that gun."

But Sally was only one young girl and could not stand off the savages forever. Rabb's mill grant was the northernmost grant in Austin's colony, and the continued theft of horses and corn by the Indians forced him out, forestalling the erection of his mill until the early 1830's. The entire family moved down the Colorado to a more settled area known as Egypt, upriver from present Wharton, where Joseph Newman and two of the Rabb sons obtained titles to their grants in the summer of 1824. Lean venison, bear meat, and honey constituted their diet until the men could burn off a canebrake and make a crop from corn planted with a sharpened stick. Sally spent her formative years here, without the benefit of any formal schooling. The death of her father in early 1831 may well have forced her into early maturity and marriage. Sally's independent spirit is reflected in the first document of record involving her, entered in the Records of Marks and Brands of DeWitt's Colony at Gonzales on September 25, 1833, which reads:

Sarah Newman wife of Jesse Robinson requests to have her stock mark and brand recorded which she says is as follows, Ear mark a swallowfork in the left and an underslope in the right and her brand the letters, J N which she declares to be her true mark and brand and that she hath no other. Sarah (herXmark) Newman [Records of Marks and Brands in the District of Gonzales for 1829, DeWitt's Colony" (County Clerk's Office). Gonzales, Texas, p. 51.]

The instrument makes clear that the brand is hers and appears on her livestock. Since her father died only two-and- a-half years before, it is obvious that the brand, her father's initials, as well as the cattle which bore it, was hers by inheritance. A modern Newman descendant said that her older brother, William, let things slide and the father's property wasn't divided for some time after his death. Sally finally told her brother, "William, I'm going down and cut out my part of the herd. If you want yours I will bring them." Although William told her to leave his, she proceeded to cut her share of the cattle from the herd. Her mark in lieu of a signature attests to her lack of any formal education. Like her mother and many other young women on the frontier, Sally became the wife of Jesse Robinson at sixteen. The young couple resided on Jesse's grant in DeWitt's colony on the San Marcos River above the town of Gonzales. Their marriage was as yet unformalized, but they may have followed the common practice in colonial Texas of signing a marriage bond. In her later divorce petition, she declared they were married on October 13, 1833. Nine years later, in March, 1838, a wedding ceremony was performed and recorded in Colorado County, but this formality may have related to land titles Jesse was claiming for his military service.

It is abundantly evident that Jesse was a staunch fighting man. He migrated to Texas in 1822 and in the spring of 1823 joined a company of volunteers, predecessors of the Texas Rangers, organized to protect Austin's colonists from Indians. In March, 1824, he and several others rescued the Rabb and Newman families from 180 Waco and Tawakoni Indians who had surrounded their house, speared and ate their largest beef, and burned fires in the yard throughout the night. This may have been Jesse's introduction to Sally, although he was twenty-four and she was only a child of six or seven years. He continued soldiering after their marriage and was a hero of the Texas Revolution. As one of Sam Houston's elite, he charged across the plains of San Jacinto and according to legend fired the shot that killed the cannoneer manning the center of Santa Anna's line. During the following summer of 1836, he served in Captain Lockhart's spy company of mounted volunteers, saw service again in August, 1841, under Captain January, and in September, 1842, participated in the Woll Campaign under Captain Zumwalt.

From the available evidence, both Jesse and Sally were contentious, and while he had an outlet through forays against Indians and Mexicans, he was the only available target for her wrath. Jesse sued for divorce in 1843, calling her a great scold and termagant. He charged Sally with adultery, particularly with one Brown, and of harboring and feeding Brown in an old wash house, to Jesse's great shame. He recited that she had abandoned him in December, 1841, and had taken one of their children. Sally responded that she was compelled to separate from him because of his excessively cruel treatment. Her petition charged him with wasting her inheritance and asked that the twenty head of cattle and other property she brought into the marriage be restored to her. Both sought custody of the two children, nine-year-old Nancy and six-year old Alfred. Following the trial, the jury rendered its verdict that all property be divided equally and did not rule on child custody. Eleven days after the divorce, Sally married George H. Scull on March 17, 1843. While Scull's name remained attached to her despite her three later husbands, little is known of him. He was a gunsmith by trade and had served in a company of volunteers from Austin County in 1836. He and Sally took up residence on her strip of inherited land near the Egypt settlement in present Wharton County.

December 30, 1844, stands as a turning point in Sally's life. On that day she and Scull sold the last 400 acres of the land inherited from her father together with a yoke of steers, four cows, twenty hogs, a mule and a bay colt, and Scull's full set of gun maker's tools and farming implements. On the same day Jesse Robinson filed a petition in the District Court of Colorado County alleging that she and Scull had forcibly abducted young Nancy Robinson and refused to surrender her to Jesse. It appears that Sally had given up a permanent home to be with her daughter and may now have begun her life on the road. Legend is that Sally placed Nancy and later her son Alfred in a convent in New Orleans to be educated, then Jesse located the daughter and moved her to another convent, with Sally later repeating the process. By tradition, the contending parents switched the children between convents several times. Sally was devoted to her children and always maintained contact with them. While Sally's legend has largely survived through frontier mothers threatening their children with "You better be good or Sally Skull will get you," stories of her affection for all children are legion. When she called at a house for a coal to kindle her campfire, she would admire and pet the new baby. Other stories passed down through families tell of her taking young children to see a train, or to help her catch a wild hog, or to travel on short journeys with her. Her attempts to educate her children may have occupied her time in the latter half of the 1840's, for few records of her activities during these years have been located. She reappeared in Wharton County in January, 1849, to acknowledge a deed to an earlier land sale and stated that she was then a single woman. Scull simply drops from the record without enough evidence to give him a personality. Although Sally declared in 1849 that he was deceased, he placed his mark on a legal instrument in northeast Texas in 1853.

By the fall of 1850 she was in DeWitt County, where the census taker found her living next to the family of Joe Tumlinson, husband of her sister Elizabeth [household 196, age 33 born Illinois]. She recorded her brand "M" in DeWitt County in April, 1851, but in 1852 moved to Nueces County to set up a permanent base of operations at Banquete. She attended Henry Kinney's great fair at Corpus Christi that year and when John S. Ford wrote his memoirs years later, he recalled seeing her in action. The last incident attracting the writer's attention occurred while he was at Kinney's Tank, wending his way homewards (from the fair). He heard the report of a pistol, raised his eyes, saw a man falling to the ground, and a woman not far from him in the act of lowering a six-shooter. She was a noted character, named Sally Scull. She was famed as a rough fighter and prudent men did not willingly provoke her in a row. It was understood that she was justifiable in what she did on this occasion; having acted in self defense. [John S. Ford, Memoirs (Austin: The University of Texas Archives) IV, p. 645.]

This gunfight in the presence of numerous visitors at Kinney's Fair must account for the spread of her reputation of violence. While Ford did not record his memoirs until many years later, a European tourist reported the lobby talk of a hotel in Victoria in December, 1853, and published it in 1859 in his journal of the tour. He doesn't mention Sally by name but there can be no question of her identity and this seems to be the earliest contemporary description of her activities. The conversation of these bravos drew my attention to a female character of the Texas frontier life, and, on inquiry, I heard the following particulars. They were speaking of a North American amazon, a perfect female desperado, who from inclination has chosen for her residence the wild border-country on the Rio Grande. She can handle a revolver and bowie-knife like the most reckless and skillful man; she appears at dances (fandangos) thus armed, and has even shot several men at merry-makings. She carries on the trade of a cattle-dealer, and common carrier. She drives wild horses from the prairie to market, and takes her oxen-waggon, alone, through the ill-reputed country between Corpus Christi and the Rio Grande. [Julius Froebel, Seven Years Travel in Central America, Northern Mexico, and the Far West of the United States (London: Richard Bentley, 1859), p. 446.]

Sally was in full operation as a horse trader and freighter by the early 1850's. Banquete, where she headquartered, is today a sleepy village on State Highway 44 and the Tex-Mex Railroad about twenty miles west of Corpus Christi. In her day its dependable source of water from Banquete Creek made it an important stop on the first hug-the-coast Texas highway, the old Camino Real running northward from Matamoros to Goliad and beyond. The growth of her business at Banquete is measured in the early Nueces County tax rolls, keeping in mind that horse traders and cow people are not noted for their accuracy in rendering all their livestock to the tax collector. The 1852 tax roll listed only four horses and four head of cattle in her name. In 1853 her assets appear on the rolls under the name of John Doyle, whom she married on October 17,1852, as one horse, four cattle, two yoke of oxen and a wagon, indicating more emphasis on freighting. Her operation continued to expand in 1854 when she is listed as Sarah Doyle with thirty-three horses, fourteen cattle, four yoke of oxen and a wagon. The following year, in July, 1855, she purchased 150 acres of land on Banquete Creek.

She recorded her brand at the Nueces County courthouse in October, 1853. Today her brand probably would be called the Flying J, but properly it is the J Flor de Luz. A few years back an old rancher failed to identify it by oral description but seeing it traced in the dirt in the time honored fashion, remarked, "Aw hell, that's the J Fly Loose." And more than likely it was the J Fly Loose when Sally ran it along the Banquete Creek. Together with her cousin, John Rabb, and his friend, W. W. Wright, Sally made Banquete an important horse trading and ranching center. She probably enticed the pair to come south from Karnes County to the greener pastures along Banquete Creek where in November, 1857, Rabb acquired the first of his numerous tracts of Nueces County land. He ran great herds of cattle bearing his Bow and Arrow brand and increased his holdings to the extent that after his death in 1872, his widow, Martha, enjoyed the title of Cattle Queen of Texas. The Rabbs are long since gone from Banquete Creek but Wright, known as "W 6" from his brand, left numerous descendants who still live and run cattle on parts of his original holdings along the lower Nueces River north of Banquete. His great grandchildren today own what may be the world's largest longhorn herd. The ribs of these modern herds are burned with Rabb's Bow and Arrow rather than the family's original W 6 brand.

A few old timers still recall tales of how Sally and W. W. Wright dedicated themselves to outfoxing the other. She drew first blood by swapping him a horse with only one good eye. As the nag passed behind Wright's house and approached his underground cistern on its blind side, it stumbled and plummeted headlong into the ranch drinking water. The poor horse drowned and left Wright with the problem of removing the carcass and hauling in water until the next rain. But W. W. found sweet revenge. Horse races formed a major diversion at Banquete and most cowmen kept a fast horse or two to match against anyone who thought he owned a faster one. Sally naturally always kept a good race horse and usually cleaned the boy's plows. Somewhere Wright picked up a crowbait with the descriptive name of Lunanca, a good Spanish word meaning a horse that is "hipped" or with one hip knocked down. When Sally next returned to Banquete, he challenged her to a match race. She seized the chance to humiliate him again, and laid down $500, high stakes for that time, but W. W. covered. Lunanca's appearance fit his title, one hip drooped sadly below the other, but when he crossed the finish line, he was so far ahead that Sally could not distinguish the difference in elevation of his two rear joints. Lunanca was one of Sally's few mistakes in judging horses. One old-timer recalled that she could out-trade anybody and her innate ability with and knowledge of horses gave her a distinct advantage. She acquired herds of up to 150 horses as far south as Mexico and traded them along the Gulf coast all the way to New Orleans. Except for the two six-shooters at her belt and a few Mexican vaqueros, she traveled the trading route alone. No one was permitted to inspect or cut her herds.

Many are the tales of her methods in acquiring her stock. She paid for purchased horses with gold carried in a nosebag draped over her saddle horn. Some hinted darkly that she didn't buy all her animals. One accusation was that after she visited the ranches in a neighborhood, raiding Lipan and Comanche Indians drove off the best horses which later turned up in her herds. Jealous wives spread the story that while she visited and made eyes at their men at the house, her vaqueros would be riding the pastures running off the horses. Although her first three marriages occurred roughly at ten-year intervals, she acquired three of her five husbands within a span of eight years during the 1850's. Numerous legends survive that she killed one of her spouses, and if she did, the unfortunate one was either George Scull or John Doyle. Both simply disappear from the record. Fertile minds have been devoted to the details of how she lost a husband. With her reputation as a marksman, one bullet should have accomplished the deed, but there are variations. One tale is that he intended to get her and laid in ambush, but made the fatal mistake of missing on his first try. They duelled for several minutes, before her superior aim prevailed, and he lost the contest.

Another improbable version has it that the couple spent the night at a Corpus Christi hotel after taking in a fandango. When he could not arouse her the next morning, he finally poured a pitcher of water on her head. Before she was fully awake she had grabbed her pistol, pulled the trigger, and lost a husband. She admitted she wouldn't have done it had she known it was him. Rather than doing him in with her six-shooter following the Corpus Christi fandango, it is sometimes told that as he stopped for another drink at the whiskey barrel, she shoved his head into the potent liquid. Crying, "There, drink your fill," she held him under until he drowned. Which leads to the yarns of accidental drownings during river crossings. As they approached a swollen river while on a freighting trip, the husband walked onto the ferry to stop the ox team and wagon. The oxen came down the steep bank with such force that he could not control them and all shot across the ferry and into the surging stream. Man and beast all drowned and Sally reportedly observed that she would rather lose her best yoke of oxen than her man. Others told it about that her husband chose to risk drowning rather than face Sally's ire after losing the team and wagon. A possibly older tale goes that she ordered her vaqueros and her husband to cross the river on a big rise. The husband and his horse were swept away and he drowned. When one of her Mexicans asked if they should search for the body, she replied, "I don't give a damn about the body, but I sure would like to have the $40 in that money belt around it."

If she did kill one of her spouses, it wasn't the fourth one, Isaiah Wadkins. This marriage was short and anything but sweet. In her divorce petition filed in 1858, she stated that they married on December 20, 1855, but that she abandoned him on May 28, 1856, after he beat her and dragged her nearly two hundred yards. Her petition accused him of living openly in adultery with other women. Wadkins was served in Rio Grande City, and in granting Sally the divorce, the jury found that her charge of his living there openly in adultery with one Juanita was proven to be true. Her accusation was so well proven that the next Nueces County Grand Jury indicted Wadkins for adultery. While the date of her fifth and final marriage to Christoph Horsdorff has not come to light, they were living as man and wife by December, 1860. It was a December and May affair, she was in her early 40's and he in mid 20's. Everyone called him "Horsetrough" for obvious reasons and as one old-timer remembered him, "He wasn't much good, mostly just stood around." Legends abound that he finally killed her.

The outbreak of the Civil War created an opportunity for which Sally had spent years in training. The Union blockade of Southern ports virtually terminated ocean traffic between the South and Europe, but the mills of England demanded southern cotton while the Confederacy's survival depended on European manufactures. International law forbade the blockaders interfering with Mexican commerce and Texas cotton moved out freely in ships loaded on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. Sale of the cotton provided funds for purchase of military supplies shipped into Mexico from Europe. The ancient Camino Real north from Matamoros became the Cotton Road, the lifeline of the Confederacy. Alleyton, near present Columbus on the Colorado and only a few miles north of Sally's childhood home, anchored the northern end of the Cotton Road. The railroad from Houston terminated at Alleyton and thousands of bales of cotton arrived there by rail to be loaded on wagon trains for the dusty journey overland to Matamoros. On the backhaul, the lumbering wagons arrived at Alleyton loaded with government stores to be shipped throughout the South by rail.

Generally ten oxen or six mules pulled a wagon loaded with ten bales of cotton, although more animals were often required in the deep sands south of Banquete. The dense chaparral of mesquite and prickly pear bordering the road north of Brownsville turned snow white with bits of cotton snagged from the endless trains. Long before the war, Sally knew every meander of the road like the back of her hand. Her headquarters at Banquete provided an ideal base of operations at midpoint of the road. She gave up horse trading for the more lucrative enterprise of hauling cotton and fitted out several wagons for a mule train. Her Mexican vaqueros became teamsters and she always accompanied her wagon train.

John Warren Hunter remembered meeting her in Lavaca County on the Cotton Road:

My visitor was a woman!---I met Sally at Rancho Las Animas near Brownsville, the year before and subsequently had seen her several times in Matamoros, and strange to relate, she knew me. --- Superbly mounted, wearing a black dress and sunbonnet, sitting as erect as a cavalry officer, with a sixshooter hanging at her belt, complexion once fair but now swarthy from exposure to the sun and weather, with steel-blue eyes that seemed to penetrate the innermost recesses of the soul-this in brief, is a hasty outline of my visitor Sally Skull!Sally Skull spoke Spanish with the fluency of a native, and kept in her employ a number of desperate Mexicans whom she ruled with the iron grasp of a despot. With these she would make long journeys to the Rio Grande where, through questionable methods, she secured large droves of horses. These were driven to Louisiana and sold. This occupation was followed until the breaking out of the Civil War, after which Old Sally fitted out a mule train of several wagons, with Mexican teamsters, and engaged in hauling to the Rio Grande. With all her faults, Sally was never known to betray a friend. [John Warren Hunter, Heel-Fly Time in Texas: A Story of the Civil War Period (Bandera: Frontier Times, 1936), pp. 57-58.]

Her slatted sunbormet was ordinarily her only bow to femininity when on the road. She rode astride and men's clothes of no special kind made up her everyday working garb. At times however, her dress changed for practical or even esthetic reasons. Certainly she had rawhide leggings for working in brush and one witness remembered her in a buckskin shirt and jacket. At other times she donned chibarros, apparently long bloomer-like garments tied at the ankles with draw strings, sometimes of rawhide or of coarse brown cloth in the summer but changed to bright red flannel for winter. Her grandchildren remembered playing with a fancy wrap around riding skirt and two French pistols which she could conceal in the skirt's folds. Her working costume was customarily accented by the two six-shooters holstered on a wide leather belt.

Even during her constant wartime travels, Sally maintained contact with her children. The Cotton Road passed near the home of her daughter, Nancy, at Blanconia in Bee County and many legends of Sally come from this area although there is no evidence that she ever lived there. Her son, Alfred, ranched about twenty miles northwest of San Patricio, where the road crossed the Nueces River. A moving reminder of the bitter days of the Civil War and of Sally survives in a letter from Alfred to his wife. Alfred rode with a Texas cavalry company and wrote hurriedly from near Port Lavaca in December, 1863, when Union troops had captured Brownsville, occupied the island along the lower Texas coast, and threatened to overrun the southern tip of the state. He spoke of his arduous duties as his company ranged in the face of the Yankee peril, told his wife she was in great danger, and advised her to go east to Lavaca County with all the horses she could find. He wrote on,

"Mother (could anyone refer to this two-gun terror as 'mother'?) promised me that she would assist you to get away. -- -I saw mother at King's Ranch but had not time to speak to her but a few minutes." [Dudley R. Dobie, "Lagarto Near Vanishing Point, Once Flourishing College Town," San Antonio Express (November 18,1934).]

But the war finally ended and the written record of Sally Skull ceases soon after. Sources that would have provided details on two intriguing events in her life shortly after the war went up in the smoke of two burned courthouses. One of the incidents shows up in the District Court minutes of Goliad County which record that on May 4, 1866, the Grand Jury of Goliad County indicted her for perjury. She certainly obtained her right to a speedy trial for on May 11 a jury rendered its verdict that she was not guilty of the charge. The specifics of the alleged perjury are unknown, for all records of the case other than the bare facts recited in the minutes were lost when fire destroyed the Goliad County Courthouse. The brief notations of this trial are the last official records relating to Sally before she disappeared. Minutes of the San Patricio County District Court give a clue to the date of her disappearance, but again the Pleadings in the case were lost when the San Patricio, County Courthouse burned. In the October, 1859, session of the court, Jose Maria Garcia filed suit against Sarah Wadkins and her former husband, Isaiah, for reasons now unknown. The suit was not pursued and minutes of the court reflect that it was continued at each session all through the Civil War years. Finally in April, 1867, the case was again continued with the cryptic notation that "death of Defendant suggested."

Nueces County brand records lend another clue that she had disappeared in the late 1860's, for her son Alfred and the two sons of her deceased daughter Nancy recorded her brand in their names in June, 1868. But to confuse the issue, minutes of the San Patricio County District Court show that the case there was dismissed in October, 1868, on motion of the defendants, that is Sally and her former husband, Wadkins. Was the case dismissed by the lawyer representing her or did she resurface in the fall of 1868? In any event she disappears from the record soon after the Civil War. Some say she rode away from Banquete with Horsdorff and that although he returned she never did. Others say he killed her. A man named McDowell claimed to have seen a boot sticking up from a shallow grave between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. When he investigated he discovered her body; obviously she had been murdered. No one can prove that Horsdorff did it, but he certainly didn't live with her long after the war. He had moved north and remarried by July, 1868.

But was she really killed or did she just decide to abandon her old haunts and find a new life elsewhere? And when did she disappear? Some say she was seen around Goliad or Halletsville in the 1870's, which would rule out her death at the hands of Horsdorff. This writer has talked with two elderly citizens, both born in the 1870's and both in possession of their faculties, who claim they saw her as children. One of these two, Mr. Charley Jones of Beeville, recalled that he and his brother would throw silver dollars in the air for her to shoot holes in them with her pistols. The boys would beg her for a perforated coin but she would say, "No, I will take it home, patch it up and use it." If she wasn't murdered but disappeared on her own, the most likely theory is that she went west and lived out her days near El Paso, probably with a Newman relative. This story persists in one branch of the Newman family. J. Frank Dobie, writing of his early days as a school teacher at Alpine, lends additional credence to this story. He wrote that Alice Stilwell Henderson, who ranched in the El Paso area and possessed many of Sally's attributes in administering her own affairs and righting her own wrongs, sat up nights writing the life of Sally Skull. Mrs. Henderson as a child may have known Sally or could have written the story as Sally related it first hand in old age. Unfortunately her manuscript disappeared years before Dobie learned of it.

So let Mr. Dobie write Sally Skull's epitaph. He wrote "Sally Skull belonged to the days of the Texas Republic and afterward. She was notorious for her husbands, her horse trading, freighting, and roughness." And her death remains as much a mystery as most of her life. [J. Frank Dobie, "A School Teacher in Alpine," Southwest Review, XLVII (Autumn, 1962), pp. 273-274.]

Our Thanks to

Dan Kilgore

for the story

|

TEXAS LEGENDS

Sally Skull - The Scariest Siren in Texas |

It was as a volunteer in a posse dedicated to the protection of Austin colonists that Jesse

first met Sally, then still a little girl. The posse rescued the Newmans from 200 Waco and Tawakoni

Indians who were trying to burn them alive. Just

imagine the heroic sight of Jesse driving off the marauding savages and coming to the rescue of the Newmans. That would

have remained in the mind of any little girl, as it did in Sally's. When she got older, she would marry her hero.

In 1839, Jesse received 640 acres of land for his participation in the battle of San Jacinto and he was present when

Santa Anna surrendered to General Sam Houston. In addition he received a certificate for 320 acres in 1838 for serving

in the army from March to June 1836, but sold it for $50. That may have been the influence of his new wife, 16-year-old

Sally, whom he had married in May of that year. Jesse and Sally subsequently had two living children, Nancy (more about

her later) and Alfred, who became a Texas Ranger and fought

in the Civil War.

No matter Mr. Robinson's heroic deeds, he became famous more for being the first husband of Sally Scull than for any

brave exploits in defense of his kin and country. Legend tells us he should have received a great deal of land just for

putting up with Sally, who was not blessed with a kind, serene, wifely nature.

An excerpt from the memoirs of legendary

Texas Ranger Colonel John S. "Rip" Ford lends credence to

the legend that she would soon become:

An excerpt from the memoirs of legendary

Texas Ranger Colonel John S. "Rip" Ford lends credence to

the legend that she would soon become:

"The last incident attracting the writer's attention occurred while he was at Kinney's Tank, wending his way homewards from Corpus Christi Fair, 1852. He heard the report of a pistol, raised his eyes, saw a man falling to the ground and a woman not far from him in the act of lowering a six-shooter. She was a noted character named Sally Scull. She was famed as a rough fighter, and prudent men did not willingly provoke her into a row. It was understood that she was justifiable in what she did on this occasion, having acted in self defense."

It wasn't only self-defense that got Sally riled up enough to shoot. She was described as "a merciless killer when aroused" and there were those who said it didn't take much to arouse her. She decided who needed killing and obliged those hapless men who fell into that unfortunate category. Occasionally, she just had a little gunslingin' fun, like the time word got back to her of nasty remarks a stranger had made behind her back. She found the man and menacingly snarled, "So you been talkin' about me? Well, dance, you son of a bitch!" and began blasting away at his boots with her six-shooters sounding like a Gatling gun and aiming at his fast-moving feet like they were a pair of glass bottles standing still on a stone wall. This caused him to do a mighty fast dance in the dusty street. It sure couldn't have been a waltz. Nobody knows the original remark that set Sally off but it must've been awful insulting.

Another time, Sally ran into a freighter who

owed her money. She grabbed an ax and said, "If you don't pay me right now you son-of-a-bitch, I'll chop the Goddam

front wheels off every Goddam wagon you've got." He did the only thing possible -- he came up with the money, paid

Sally, and lived to tell the tale. Presumably.

She could shoot equally skillfully left- or right-handed, and carried a black-leather-handled, tooled whip with

which she could snap the heads off innocent flowers or the skin off the back of a man she believed did her wrong. Not

only was she adept at using the six-shooters in the cartridge belt on her hips (French pistols hidden beneath her

skirts, when she wore skirts), she carried a rifle and was as good a sharpshooter as

Annie Oakley,

long before

Annie was born.

Jesse divorced Sally in 1843 calling her "a great scold, a termagant, and an adulterer," naming as her lover a man called Brown, a fellow who, according to court records, Sally had been harboring in an outbuilding. Gossip suggests "Brown" might have actually been Sally's next husband, George Scull.

Jesse also claimed Sally abandoned him in December 1841 and Sally countersued, charging that she was the victim of his excessively cruel treatment, claiming he wasted her inheritance and demanding he pay back her dowry. Eventually, she left town with her two kids in tow, planning to earn her living by trading horses, leaving Jesse to continue raising race horses in Live Oak County. (By some accounts, Sally was able to leave with only one child, 6-year-old Alfred, after a bitter, unresolved custody battle with Jesse.)

That same year, 1843, Sally married George H. Scull (the ubiquitous Mr. Brown?), a mild-mannered gunsmith known for his "gentle nature." Poor George was a law enforcement volunteer serving residents of Austin County, and the Sculls lived on land near Egypt that Sally had inherited from her father. A year and a half later, George and Sally left town in a hurry, reportedly due to rising heated hostilities between Jesse and Sally concerning custody of the children.

When they moved, George and Sally sold the last 400 acres of her inheritance, George's prized gun maker's tools, and all the farm equipment. On December 30, 1844, she petitioned for custody of 9-year-old Nancy. Custody was refused, so George and Sally did what they thought best at the time. They kidnapped Nancy and headed for New Orleans. There, Sally placed both children in a convent.

"In a rage, Jesse sniffed out their trail and followed their tracks..." He pulled them out of the convent and placed them in a different New Orleans convent but he didn't reckon on Sally's tenacity. She abducted them yet again and placed them in a third school.

Scull vanished around 1849 and, when asked about him, Sally answered tersely, "He's dead." People were more afraid of Sally than inquisitive about George, and stopped asking. However, records in northeast Texas indicate that around 1853, someone made George's mark on legal papers, leaving a question about his death. We can speculate that he possibly ran off as far as he could from his screaming spouse, or that he was six feet under and that the mark was a forgery. If Jesse were pushing up daisies, we can rest assured that they would've had their sweet little daisy heads snapped off by a black widow wielding a long black-handled whip.

In 1852, Sally Skull (Sally herself changed the spelling from Scull to Skull because she liked it better) bought a 150-acre ranch in Banquete, Nueces County, and married John Doyle who helped her turn Banquete into a trade and ranching center. One of their friends was a practical joker named W.W. Wright, who loved to engage Sally in a game of one- upmanship. The following excerpt is fromOutlaws in Petticoats:

'Once Sally sold WW a horse with a blind eye, a feature John missed when examining the animal. That afternoon, the nag was meandering behind Wright's house when the poor creature stumbled on the underground cistern. The horse plummeted headfirst into he ranch drinking water, where it met a watery death. Wright was left with the huge task of trying to remove the carcass that lay deep down in the cistern, out of reach of normal ranch equipment.'

Wright thirsted for revenge. He challenged Sally to a race, a favorite diversion in Banquete. In clear view, Wright paraded his newly acquired horse, Lunanca. Sally knew that the name was Spanish for a horse that is "hipped," or with one hip raised above the other. No fool, she saw this as a chance to take her friend once again. She knew there was no way Lunanca could outrun her mare. She laid down $500, high stakes at the time, and Wright eagerly covered. The town watched as the sad-looking horse hobbled to the starting line. When the shot fired, Lunanca, crazy with excitement, took off like a bullet, leaving Sally's horse in a cloud of dust. A seasoned horse trader, Sally had been taken by a mischievous cohort and a second rate horse with bad hips who loved to run.'

Like husband Scull, husband Doyle disappeared

leaving behind two speculative and

colorful versions of his demise. 1) He ambushed and tried to kill his viper-tongued wife but she got to him first. 2)

Sally and Doyle were doing a drunken fandango in Corpus Christi and stayed overnight in a hotel. Unable to awaken her

next morning, Doyle resorted to pouring a pitcher of cold water on her head. Waking up instantly but still hung over,

she grabbed a pistol and plugged him deader'n a doornail. By accident, she said.

Like husband Scull, husband Doyle disappeared

leaving behind two speculative and

colorful versions of his demise. 1) He ambushed and tried to kill his viper-tongued wife but she got to him first. 2)

Sally and Doyle were doing a drunken fandango in Corpus Christi and stayed overnight in a hotel. Unable to awaken her

next morning, Doyle resorted to pouring a pitcher of cold water on her head. Waking up instantly but still hung over,

she grabbed a pistol and plugged him deader'n a doornail. By accident, she said.

Yet a third version for those who don't believe either of the aforementioned, is that one night, Sally caught her drunken husband swilling whiskey from an open barrel; she pushed his head down and shouted, "There! Drink your fill!" This, it is said, is how he really died.

If you don't like any of those theories, how about the one where Sally, Doyle and a group of vaqueros on a freighting trip, came upon a swollen river. Doyle walked down to stop the oxen and wagon from sliding down the deep bank and into the surging water, except the team was unable to stop, and slid down taking Doyle with them. They fought a losing battle with the raging river and all drowned. For this story, Sally is alleged to have said "I would rather have seen my best yoke of oxen lost than my man." Some say Doyle could have swum free but was too frightened of arousing his wife's ire at his having lost the team of oxen.

In the mid-1850s a European tourist recorded her activities and reputation.

"The conversation of these bravos drew my attention to a female character of the Texas frontier life, and, on inquiry, I heard the following particulars. They were speaking of a North American amazon, a perfect female desperado, who from inclination has chosen for her residence the wild border-country on the Rio Grande. She can handle a revolver and bowie-knife like the most reckless and skillful man; she appears at dances (fandangos) thus armed, and has even shot several men at merry-makings. She carries on the trade of a cattle-dealer, and common carrier. She drives wild horses from the prairie to market, and takes her oxen-wagon, along through the ill-reputed country between Corpus Christi and the Rio Grande."

About 1855, Sally married husband #4, Isaiah Wadkins, but left him after only five months because, according to court records, he beat and dragged her nearly 200 yards. He must've been pretty darned strong, or else maybe he had her tied to the leg of a horse. The records don't say. Sally also proved he was actually living with a woman named Juanita. Her divorce was granted on the grounds of cruelty and adultery.

Some of her neighbors suspected that she was

(gasp) a horse thief,

and did the dastardly deed of stealing stock from her friends. Her method allegedly began with a friendly visit and,

while Sally talked amiably with her host, her vaqueros were casing the ranch, cutting barbed wire and running the

neighbor's horses off. Indians took the fall for this

treachery. Some even said bands of Comanche were on Sally's payroll, so she got the stolen horses every which way she

could, and they were promptly given her Bow and Arrow brand, though some sources have her brand as Circle S. It was also

said that her brands might not stand close inspection. However, entered in the Records of Marks and Brands of DeWitt's

Colony at Gonzales on September 25, 1833, we find the following:

Some of her neighbors suspected that she was

(gasp) a horse thief,

and did the dastardly deed of stealing stock from her friends. Her method allegedly began with a friendly visit and,

while Sally talked amiably with her host, her vaqueros were casing the ranch, cutting barbed wire and running the

neighbor's horses off. Indians took the fall for this

treachery. Some even said bands of Comanche were on Sally's payroll, so she got the stolen horses every which way she

could, and they were promptly given her Bow and Arrow brand, though some sources have her brand as Circle S. It was also

said that her brands might not stand close inspection. However, entered in the Records of Marks and Brands of DeWitt's

Colony at Gonzales on September 25, 1833, we find the following:

Sarah Newman wife of Jesse Robinson requests to have her stock mark and brand recorded which she says is as follows, Ear mark a swallowfork in the left and an underslope in the right and her brand the letters, J N which she declares to be her true mark and brand and that she hath no other. Sarah (herXmark) Newman [Records of Marks and Brands in the District of Gonzales for 1829, DeWitt's Colony" (County Clerk's Office). Gonzales, Texas, p. 51.

(The instrument makes clear that the brand is hers and appears on her livestock. Since her father died only two-and-

a-half years before that time, it is obvious that the brand, her father's initials, as well as the cattle which bore it,

was hers by inheritance).

Sally began to make the dangerous journey across the border into Mexico for horses. Usually alone, carrying large sums of gold in a nosebag hanging over her saddle horn, she bought herds of wild mustangs, which she frequently sold in New Orleans.

Most women would not have dared to do anything so fraught with peril, but Sally was not most women. She encountered a problem only once, in the territory of Cortina, when a bandit and self-proclaimed governor jailed her for a few days. Sally seemed to regard it as a sort of vacation and just sat and waited for her vaqueros to arrive.

When the Civil War broke out, Sally saw a surefire way to make even more money: Texas cotton, sorely needed by European manufacturers, through Mexico to Europe and, on the way back, arms and other military supplies from Europe through Mexico to the south by rail. The Camino Real north from Matamoros to Alleyton where the Houston railroad line ended, formed what became known as The Cotton Road. Banquete was the midway point.

When Sally was traversing The Cotton Road with her teamsters, her favorite outfit was a buckskin shirt, jacket and chibarros, long rawhide or coarse cotton bloomers tied at the ankles with drawstrings. During winter, she often wore chibarros of bright red flannel. Her grandchildren later remembered that she sometimes "sported a fancy wrap-around riding skirt. Her two ever-present French pistols were always hidden in her skirt when she wasn't sporting her holstered six-shooters."

Unlike Lottie Deno, Sally was no fashion figure. Old newspapers report her as dressing solely in rawhide bloomers, making it easier for her to ride astride Redbuck, like a man. Others say she rode sidesaddle and wore a long skirt or dress and a bonnet. John Warren Hunter wrote "I met Sally at Rancho Las Animas near Brownsville... Superbly mounted, wearing a black dress and sunbonnet, sitting as erect as a cavalry officer, with a six-shooter hanging at her belt, complexion once fair but now swarthy from exposure to the sun and weather, with steel-blue eyes that seemed to penetrate the innermost recesses of the soul -- this in brief is a hasty outline of my visitor -- Sally Skull!"

Sally spoke fluent Spanish, had a fondness

for Mexicans, and hired them to work

in her business of freighting cotton by wagon train to Mexico in exchange for guns, ammunition, medicines, coffee,

shoes, clothing, and other goods vital to the Confederacy. She had a reputation of ruthlessness and of ruling the armed

trail hands with the crack of her whip, fueled by a hasty and nasty temper. Nonetheless, the trail hands (teamsters)

developed a healthy respect for such a woman who knew so many cuss words, the type of words that would "scald the hide

off a dog." They were also impressed with her prowess with pistols. Her expert cussing also impressed a preacher Sally

met on the trail.

Sally spoke fluent Spanish, had a fondness

for Mexicans, and hired them to work

in her business of freighting cotton by wagon train to Mexico in exchange for guns, ammunition, medicines, coffee,

shoes, clothing, and other goods vital to the Confederacy. She had a reputation of ruthlessness and of ruling the armed

trail hands with the crack of her whip, fueled by a hasty and nasty temper. Nonetheless, the trail hands (teamsters)

developed a healthy respect for such a woman who knew so many cuss words, the type of words that would "scald the hide

off a dog." They were also impressed with her prowess with pistols. Her expert cussing also impressed a preacher Sally

met on the trail.

Sally was hauling freight to Mexico when she came upon the preacher who had inadvertently mired himself and his two- horse buggy down in the muddy road. All he could do was shake the lines up and down on the horses' backs, to no avail. They refused to pull. Suddenly Sally rode forward and yelled loudly as only she could, "Get the hell out of there you sons of bitches!!! Get the hell out!!!" whereupon the horses bolted, freeing themselves, the buggy and the preacher. They were seen running on down the road. The preacher managed to get himself and the buggy entrapped in the muck a second time, ran back to get Sally, and said, "Lady, will you please come and speak to my horses again?"

Sally's magnificent Spanish pony named Redbuck, was almost as famous as she was. Gifted with legendary endurance, a necessary quality for a horse who wanted to please his tempestuous owner, Redbuck was blanketed in bright colors and ridden under a fine Mexican silver-trimmed saddle. Sally failed to understand that she had passed on her affection for Redbuck to her daughter, who felt the same way about a pet dog. Nancy had been sent off to New Orleans to become a lady, and it was said that Nancy became so refined that she valued her dog above people. One day when Sally was visiting, she became enraged when the dog tried to bite her, drew her gun and blew him to smithereens. Nancy never spoke to her mother again.

Sally was at her "peak of notoriety" when she met and married husband #5, a man half her age named Christoph Hordsdorff, nicknamed "Horse Trough." One old-timer who knew 21-year-old Horse Trough described him as being "... not much good, mostly just stood around."

As the story goes, Horse Trough and Sally rode out of town together one day. Only one rode back.

Horse Trough returned alone to Banquete. "She simply disappeared," was all he said, which probably aroused more gossip than if he had admitted outright that he plugged her. Speculation abounded that he "blew off the top of her head with a shotgun" for the gold in her saddlebag. Let's face it though, if he was 21 to her 43, and good-looking enough to just have to "stand around," chances are she would've willingly handed the gold over.

A drifter later reported that as he was traveling over the prairie, he came across the body of a woman buried in a shallow grave. He first spotted it when he saw a boot sticking out of the ground, with only circling buzzards marking the spot. There was no evidence that the boot was on a foot connected to the body of Sally Skull. Presumably, Horse Trough inherited her entire estate.

What if he didn't do old Sally in after all? Records indicate that she faced perjury charges and was defendant in a

lawsuit brought by Jose Maria Garcia. Even though the San Patricio County courthouse burned down and official reports on

the case were lost forever, one form relating to the lawsuit survived. Written across the bottom was the mysterious

notation "death of Defendant suggested."

The infamous Sally Skull was portrayed in the 1989 mini-series, "Lonesome Dove" by O-Lan Jones.

In 1964 a historical marker in her honor was erected two miles north of Refugio, Texas, at the intersection of U.S. Highway 138 and State Highway 202. It reads:

SALLY SCULL

Woman rancher, horse trader, champion "Cusser." Ranched NW of here. In Civil War Texas, Sally Scull (or Skull) freight wagons took cotton to Mexico to swap for guns, ammunition, medicines, coffee, shoes, clothing and other goods vital to the Confederacy. Dressed in trousers, Mrs. Scull bossed armed employees. Was sure shot with the rifle, carried on her saddle or the two pistols strapped to her waist. Of good family, she had children cared for in New Orleans school. Often visited them. Loved dancing. Yet during the war, did extremely hazardous "man's work."

© Maggie Van Ostrand, August, 2007

About the Author:Maggie Van Ostrand's articles have appeared in theChicago Tribune, theBoston Globe, various magazines; monthly in the Mexican publication,El Ojo Del Lagoandmexconnect.com, and numerous contributions toTexas Escapes Online Magazine, from which this article was provided.