Tarrant County, TXGenWeb

The History

of Hicks Field

(Published in 3 parts, Nov. 14,

21 & 28, 2002, NW Times-Record)

Contributed by

Kenneth Klein

Staff Writer, NW Times-Record

The History Of Hicks Field

Our little corner of the County claims a rich history in military aviation. A small airfield, located on a breezy prairie north of Saginaw, trained more than 6,000 Canadian and American pilots, gunners and observers for service to our nation in World Wars I and II.

The site, known at various times as Taliaferro Field, Camp Hicks and Hicks Field, had been part of the old Hicks Ranch. The Canadians called it Taliaferro Field, after Walter R. Taliaferro, a U.S. Army aviator who had been killed in an accident. But the name changed to Hicks Field after the U.S. went to war. The name was given from Charles E. Hicks, the landowner from who the Field came from. Mr. W.G. Fuller, a WWI pilot who had flown at Hicks Field, recalled Mrs. Hicks as she "rode fence" with a Winchester rifle cradled in her arm, looking for trespassers. "I thought I could use profanity", he reminisced. "But mine was nothing compared to that old lady".

It all began on April 1917 when the United States declared war, joining other countries in World War I. But our military flying capability was small and inexperienced. The Canadians, on the other hand were already in the war with a "seasoned" air force. When the military chiefs of our two countries compared our strengths and weaknesses to fight our enemy, they saw they could help each other, and negotiated a logical contract.

The concept for a flying field located here was proposed by the Canadians. The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) needed a warm climate for winter flight training. The Americans needed help in quickly establishing flight training schools. The RFC agreed to train ten aero squadrons, both pilots and ground personnel, in exchange for facilities in Texas to cover the winters of 1917-1918. The airfield was born!

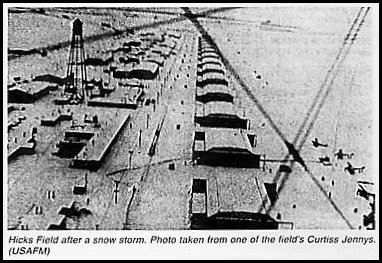

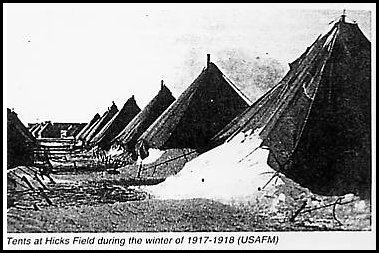

Work had to be done fast. Cattle were moved out, and construction crews worked feverishly at the site, known as Taliaferro Field, and at two auxiliary fields in Benbrook and Everman. When the trainees first arrived in November 1917, the fields were only partially complete. But training was started anyway, despite unfinished facilities, lack of water or sewer and unassembled aircraft. The first winter was difficult. Many men lived in tents in this snowy winter. A worldwide flu epidemic hit Hicks Field hard.

One cadet reported seeing a trainload of casket laden flat cars leaving Fort Worth. Despite these hardships, the skies overhead were filled with the rich, vibrant sound of throbbing airplane engines - within a month.

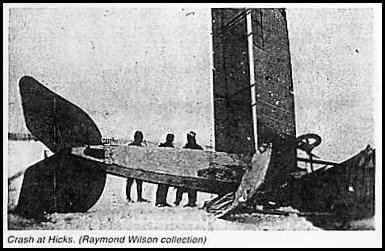

In fact, the skies stayed full of Jennys. Colonel David L. Roscoe, an early Hicks Field commander, recalls that ".....a plane landed here every 34 seconds from dawn until dark, and during the course of a day the average number of hours flown by instructors and cadets was 1,300". With that amount of flying activity, accidents were common. Although there were serious crashes, many of them resulted in little injury to the pilot or gunner (although photos of the crashes make us wonder how).

The biplane of choice was the JN-4 "Jenny". It had two open cockpits; the student manned the front, and instructor commanded from the rear. With the Curtiss OX-5 engine, it could reach a top speed of 64 MPH. Later Jennys were powered by the 180 HP "Hisso" engine, which increased it's speed to 78 MPH. The speed of these planes might make them seem like toys as compared to todays aircraft, but it must be stressed that only 14 years the first flight at Kitty Hawk occurred!

There were two versions of the Jennys flown at Hicks. The Canadian version was called the JN-4C Jenny "Canuck". The American version was the JN-4D. In dire need of flyable aircraft, the U.S. agreed to purchase 180 Jennys from the Canadians once their training was done. Only an expert could tell the difference.

Training was taught by the Canadians. The two auxiliary fields were in charge of primary flight training, including aerial maneuvers such as tailspins, loops, falling leafs, Immelmann turns and barrel rolls. But during this time, Hicks took on a new role as the primary training base for the new art of aerial gunnery. Pilots came from all over the U.S. to learn this new art, including 300 ensigns from the U.S. Navy. Gunnery was taught in a 6 week course, on the ground in special gunnery ranges and in the air - in the reliable Jenny. One of the first gun cameras were developed at this time. This allowed an evaluation of the cadets accuracy - without firing a live round. Pilots were taught how to fire from the pilots cockpit as well as the gunners cockpit. The gunners cockpit did not have a seat, but only a crossbar to sit on. There was not a "seat belt" provided, and firing the swivel-based Lewis machine gun meant standing up!

Besides molding men into lean, mean fighting machines, Hicks also molded some long lasting friendships between the Canadians and Americans. Floyd Scott, a member stationed at Hicks told a Fort Worth newspaper, "One of the most vivid memories of Hicks Field was the remarkable friendship that existed between the RFC pilots and the American flyers". Indeed, the townspeople of the surrounding communities opened their homes, their hearts and numerous facilities to the young aviators. One particular Canadian aviator, Captain Vernon Castle, was well liked by the Hicks people as well as the townspeople of Fort Worth. He was already world renown as the famed dance team of Vernon and Irene Castle. He was larger than life. He owned a Stutz Bearcat and was seen often roaring over the prairie at Hicks, accompanied by his pet monkey. Regrettably, he was killed in a plane crash at the auxiliary field at Benbrook during training exercises. Some witnesses, including William Fuller, believed that he deliberately crashed in order to avoid hitting another plane, and saved their lives. His burial was witnessed by thousands of mourners, who sadly watched the flagged draped casket pass in downtown Fort Worth. Even today, there is a street in Benbrook named in his honor.

Now with the training behind them, the aviators were to test their skills in battle. The first to leave was the 17th Aero Squadron, with 95 pilots and a full compliment of support officers and enlisted men. They departed Hicks Depot on December 17, 1917 and arrived in Garden City, New York where they were ushered by boat to Paris, France. Many of the pilots, graduating from the Jennys, became known as "Camel Drivers", namely the Sopwith Camel (Many of you are no doubt familiar with Snoopy from the popular Peanuts cartoon). Although the Sopwith was the most successful of all the planes in shooting down enemy aircraft, it's unusual handling characteristics made it very difficult to fly, and ended up giving a a good kill ratio to our own pilots. In January, 1918 the 22nd, 27th and 28th Aero Squadrons left Hicks. A month later, the 139th, 147th and 148th left to amass our fighting forces. Arriving in France, many Americans found to their surprise that were their squadrons were attached to RAF units! Many found Canadian friends they had known in Texas.

In April of 1918, the Canadians' job was done, and packed up to return to Canada. They had accumulated over 67,000 flying hours, trained 1,960 pilots, 69 ground officers and 4,150 men in various ground skills. To the whine of their own bagpipe land, a sound foreign in the land of cowboys and cattle, they marched past many of their cheering Texas friends and took their departure at the T&P Railroad Station in downtown Fort Worth.

On November 11, 1918 came news of peace. World War I was over. The men at Hicks rejoiced. One cadet, Mr. Jack Jaynes, was both elated and frustrated. He would not be able to prove his newfound training to Uncle Sam - his chance had vanished. But all was not lost! He and some fellow aviators felt that something spectacular was in order. They decided to honor the occasion with a never-to-be-forgotten air show directly into the downtown area of Fort Worth. They simulated street strafing down the avenues and between the buildings. The width of their wings often caused them to turn or bank sharply to avoid hitting the buildings. Everyone who witnessed this talent of flying skills would never forget it! (No buildings were harmed in the course of this exhibition).

In 1919, with news of the Armistice, Hicks Field was deactivated. The hanger doors were closed on an unforgettable episode in the history of American military aviation, and the chapter on WW I was closed. But the chapter wasn't closed on Hicks Field.

Hicks Field remained dormant for a time, and the remaining structures tried to stand their ground against wind and sun. Cattle roamed the areas where the taxiways and gunnery ranges once stood.

But in 1923, the Hicks Field became the site of the world's first helium plant, built by the U.S. government, and ran by the Navy (some claim that the true site was at the old FAA headquarters on Blue Mound Rd). Some of the Navy's great dirigibles, the Shenandoah, Macon, Akron and the Los Angeles - would arrive and top off their helium supplies there. Non- inflammable helium was the gas that kept these 700-foot-long monsters aloft and we had the world's entire supply back then. But over a period of time, other countries began "prospecting" for helium, and in 1929, the plant was closed due to a shortage of helium!

Hicks Field again lay dormant for many years. The weather had taken it toll on the existing structures. All that remained were two hangers, remaining as lonely sentinels from the days of previous glory. But in 1940, Europe was again at war, and Uncle Sam felt that he must be prepared. Responding to this call, Hicks Field was again opened as a training base in July of 1940. A major construction and renovation job was required for Hicks, and once completed, Texas Aviation Inc., and W.F. Long Flying School moved in. As a private flying school, it received a contract to train new cadets on the new field that was constructed. Thirty-eight new Fairchild PT-19's and PT-19A's were assigned to Hicks, and the Army Air Corps again had pilots training there. Hicks was one of the first primary flying schools in the Army Air Corps expansion program. Lt. James H. Price was the first commanding officer. The instructors were all contract civilian instructors, pilots with a long history of experience in light aircraft. They would take the cadets through the rudiments of basic flying and guide them through their first solo flights. When successfully completed, they would go to Basic Flight Training at Randolph AFB and then Advanced Flight Training at Foster Field.

This activity did not escape the eyes of the old aviators from WWI, still residing in Fort Worth and surrounding towns. They felt a certain responsibility to the new cadets at their own flying field. The World War Flyers, as the 43 old timers came to be known, sent a letter to the parents of each new cadet coming into Hicks Field. The letter assured the relatives that they would do everything possible to make the lad welcome and happy in Fort Worth. Each class was given a formal introduction to Fort Worth, and introduced them to the prettiest girls at a dinner dance at the River Crest Country Club, one of the finest in the City. This came to be a tradition on the first saturday night of the month when cadets were permitted to leave their post. This successful program greatly boosted morale.

A ten-week course of primary training continued at Hicks, and a total of 2,403 cadets were processed, and about 70% made it to the next level of training at Randolph AFB in San Antonio, Texas. In 1942, the Tarrant Field Aerodrome was built for flight training and heavy bombing operations training. In 1944 it was named Carswell Airfield, in honor of Major Horace Carswell, an aviator born in Fort Worth. He gave his own life so that the crewman on board the wounded B-24 could make it to safety. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1944. As Carswell Airfield began to grow, many operations were transferred from Hicks Field. By 1944 the war had ended and Hicks Field deactivated it's training schools.

But the gates were not immediately closed; for a few years after WWII, planes flew at Hicks. The Defense Plant Corp. used it as a base for it's sale of surplus Army aircraft. In the mid 1950's, the Texas Helicopter Division of the Bell Aircraft Company used it to test their experimental XHSL-1 twin rotor helicopter. This division later became Bell Helicopter. They moved the manufacturing facility to the abandoned Globe Aircraft Company building and used Hicks Field as it's flight test facility. After Bell left, the field was mostly used a general aviation field by civilians.

From the 1970's to present, Hicks Field began a transition from civil airport to an industrial park. Recently, it has been the focus of an investigation for environmental cleanup by the Texas Superfund.

A new airport called Hicks Airfield, which is privately owned but open to the public, was opened up a half mile north of Hicks Field. It has remained a very active airport for civil aviation.

The ravages and time and weather have taken it's toll on the old airfield. Almost any telltale signs of it's contribution to our country or the local area have all but been erased. Not even a Texas Memorial Marker has been placed here to reveal it's secrets; of what once was. The wide open Texas prairie and skies, which played host to many chapters of aviation history, had nourished many of our country's pilots. But now the roar of airplane engines can only be heard from a distance.

Bibliography

Friends Journal, Vol.24, No.1, Spring 2001, "Hicks Field, Texas WW! & WWII Flight Training Base, pgs. 18-24

Texas State Historical Association, The Handbook of Texas Online, "Hicks Field"

This page was last modified 7 Jun 2003.

Copyright © Tarrant County, TXGenWeb 2003. All rights reserved